Main Content

The Place of Many Moods:

Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century

Dipti Khera

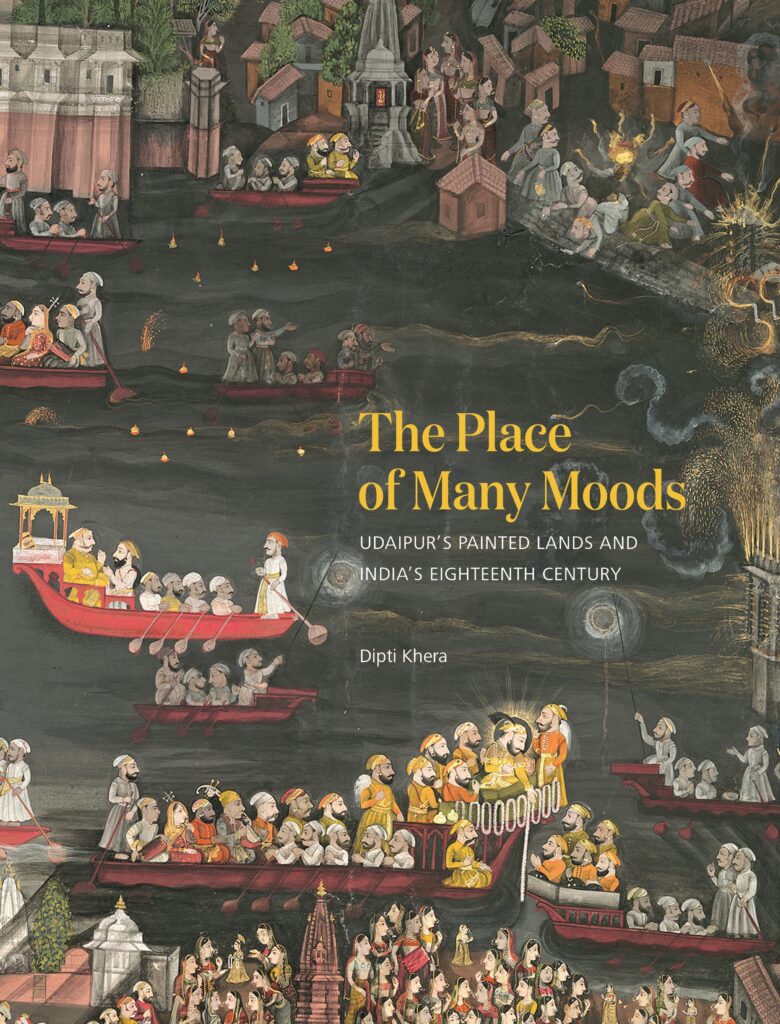

The Place of Many Moods: Udaipur’s Painted Lands and India’s Eighteenth Century (Oxford and Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020) uncovers an influential creative legacy of evocative beauty that raises broader questions about how emotions and artifacts operate in constituting history and subjectivity, politics and place. It looks at the painting traditions of northwestern India in the eighteenth century, and what they reveal about the political and artistic changes of the era.

In the long eighteenth century, artists from Udaipur, a city of lakes in northwestern India, specialized in depicting the vivid sensory ambience of its historic palaces, reservoirs, temples, bazaars, and durbars. As Mughal imperial authority weakened by the late 1600s and the British colonial economy became paramount by the 1830s, new patrons and mobile professionals reshaped urban cultures and artistic genres across early modern India. This book explores how Udaipur’s artworks—monumental court paintings, royal portraits, Jain letter scrolls, devotional manuscripts, cartographic artifacts, and architectural drawings—represent the period’s major aesthetic, intellectual, and political shifts. These immersive objects powerfully convey the bhāva—the feel, emotion, and mood—of specific places, revealing visions of pleasure, plenitude, and praise. They sought to stir such emotions as love, awe, abundance, and wonder, emphasizing the senses, spaces, and sociability essential to the efficacy of objects and expressions of territoriality. These memorialized moods confront the ways colonial histories have recounted Oriental decadence, shaping how a culture and time are perceived.

This website supplements The Place of Many Moods to create new opportunities for immersive and iterative viewing across the length and breadth of the select artifacts, many of which are studied and published for the first time here. For instance, examining up close the complex spatial composition and minute details and labels seen in the Letter of Invitation Sent to the Monk Jinharsh Suri, 1830, enables us to reflect on the continuities and discontinuities between manually unrolling and examining long paper scrolls and scrolling up and down a pixelated screen to find new cues and connections. Similarly, visually scanning across the digital images of Udaipur’s large court paintings and architectural drawings reveals meticulous brushwork and painterly effects that may be concealed in the book’s printed reproductions. In the future, I hope we can find the imaginative digital and technological means to convey the material presence and scalar specificity of these artifacts, as they were bundled and unfurled, folded and unfolded.

I look forward to learning what you discover. I welcome your thoughts on how we may deploy digital art history to pursue visually, spatially, and materially motivated historical questions in collaborative and innovative ways. The digital images are presented using the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), which was founded with the goals of providing depth of access using application programming interfaces (APIs) and it allows for better navigation between the various image viewing platforms through which museums, universities, and other cultural institutions share their images.

Jacket design by Jo Ellen Ackerman / Bessas & Ackerman Princeton University Press

In 1830, the king of Mewar and a group of regional merchants jointly sent a signed painted scroll, seventy-two feet long and eleven inches wide, as an invitation letter, a vijñaptipatra, to the eminent monk of the Jain religious community, Shri Jinharsh Suri in Bikaner. They requested that Jinharsh Suri spend the next monsoon season in their vibrant capital city, Udaipur. The custom of sending vijñaptipatra scrolls among the Shvetambara sect of Jainism owes its origin to the traditions of asking for forgiveness for sins and vowing to perform pious deeds in the future—in this case, pilgrimages to the immobile sacred sites and the mobile holy places eminent monks created by their presence.

Over the first sixty-five feet of this paper scroll, an unnamed artist from Udaipur creatively mapped a principal street of the city, painting its important palaces, temples, and bazaars. This composition shows that the painter was clearly knowledgeable in the pictorial style practiced by court artists. He added an elaborate procession to the center of the scroll, depicting the Udaipur Maharana Jawan Singh (r. 1828–38) and the British colonial agent Alexander Cobbe, creating an unusual and innovative dual axis—a long spine that is intersected continuously by horizontal cells—along which a viewer constantly navigates in order to see and understand the work.

Artists joined together multiple sheets of paper of approximately two feet in length in order to create such letter-scrolls. Considering even this simple step in its assembly, one confronts multiple questions: Did a master artist draw the complete composition, to be followed by other artists from the workshop, who filled in colors in parts of the scroll? Or did the artist paint the scroll in a continuous manner, addressing a manageable length of two to three feet at a time? If artists indeed worked in this manner, how did they manage to conceive an all-encompassing cityscape as a unified picture? Was the process therefore somewhat akin to how viewers are likely to have visually explored the scroll, looking at a limited length of the city’s map and streets at a time? Whether monks unrolled the complete scrolls on the floor for their primary audiences—the Jain pontiffs to whom the invitations were addressed—or the pontiffs held the scrolls themselves, it is possible to see only to two or three feet of the scroll in a focused manner at a time. The historical consumption of such letter-scrolls by collectives were likely aided by the hands of attendants and artists, and the words and recitations of chroniclers and poets, monks and messengers.

This image viewer works best in Chrome.

The Moods

Pictures of moods possess the overpowering ability to make places real and times memorable—to create worlds. The sheer number of commissions at the Udaipur court that negotiate between rendering the moods of real places and evoking idealized abodes far exceeded the corpus created at any of the other regional workshops. They cumulatively open our minds to the artistic, intellectual, and historical capaciousness of "bhāva of a place"—the mood of a place—as a meaningful and pertinent conceptual category.

A second IIIF image viewer holds a number of interrelated images of the moods of painted places, including current location photography, that features in The Place of Many Moods.

To trace the threads that run through the art of picturing moods, I have followed the environmental constituents—mountains, rivers, rains—that shaped Udaipur’s lands and its experience. In researching this book I have inhabited the material world of lakes and lake palaces, architectures of courtyards, and altitudes of terraces, and I have dwelled upon their imaginings in expressive media: paintings, drawings, painted letters, daily court diaries, diplomatic correspondence, and the poetry of esteemed court poets and amateurs—traveling monks who illuminate the historical paths of strolling and point of views for admiring places. I have considered these eighteenth-century intellectuals’ contemplations on the sensorial and the atmospheric. They gave voice to descriptive modes of world making that made affective images as important in rendering real places as these did in imagining poetic places. I have followed the itinerancies of objects, artistic practices, and aesthetic ideas within and between media—from painted letter-scrolls to architectural drawings created for mixed publics including British East India Company offers. In yet other instances, I have tracked the political roles and personal bonds of represented participants—kings, nobles, and colonial officers; merchants, messengers and monks; and ordinary folk and court attendants, whom painters scrupulously included to create busy images of worlds immersed in praiseworthy moods.

The mood of a place emerges as a phenomenon that was created, iterated, and circulated to do enormous work, to be powerfully effective in making worlds feel alive on paper and cohere together on land in India’s long eighteenth century.

The Dialogues

For further reading, listening, and viewing, you are invited to explore resources on the book, and related topics.

- Book’s Introduction and Index

- A conversation at the Institute of Fine Arts-NYU about The Place of Many Moods, with responses by Dr. Vittoria Di Palma, Associate Professor of Architectural History and Art History at the University of Southern California, and Dr. Kavita Singh, Professor of Art History at the School of Arts and Aesthetics of Jawaharlal Nehru University, December 4, 2020.

- “In the mood for art in India’s eighteenth century” Princeton University Press Ideas Blog (October 29, 2020)

- “Material unfurling, digital scrolling, urban strolling, c. 1830–now,” Princeton University Press Ideas Blog (January 14, 2021)

- Dr. Dipti Khera in conversation with Shrishti Malhotra, producer at The Swaddle, about the cultural importance of eighteenth-century Indian art, what lake palaces tell us about the relationship between pleasure, water, and politics, December 21, 2020. The Swaddle Podcast (December 21, 2020)

- In conversation with Dr. Anandi Silva Knuppel, a media specialist working with the American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS), and Dr. Deborah Hutton, Professor of Art History at The College of New Jersey, about AIIS fellowships, workshops, and book prizes for emerging scholars. Dipti Khera held an AIIS Junior Fellowship in 2009–10, and The Place of Many Moods was awarded AIIS’ 2019 Edward Cameron Dimock, Jr. Prize for the best unpublished book manuscript in the Indian Humanities, January 8, 2021. Click here for the podcast.

- The Courtauld Institute of Art hosted a talk on The Place of Many Moods on February 18, 2021. You can watch a recording of "The Mood of a Place: A Sensible History of India’s Eighteenth-Century Locals and Locales” here.

Acknowledgments

I thank Princeton University Press and its team for supporting this project. I am grateful to Jennifer Henel for insights on creating this book website as a supplementary resource, the website design, and IIIF work on the complex scroll artifact. Her collaborating partner, Morgan Schwartz, provided further inputs on programming needs. I want to thank Nancy Um for her guidance on this project, which proved invaluable, along with the advice of NYU colleagues Zachary Cobble, Marii Nyrop, and Jason Varone. Earlier discussions with Lyla Halsted on digitally exploring the materiality of scroll objects initiated this project, and I must thank Blair Simmons for digitally stitching the letter scroll’s images. I thank all the museums and libraries, especially Abhay Jain Granthalaya, Bikaner and Rishabh Nahata, for their generosity to use images of the artifacts in their collection.

Footer

Contact

The Author

Read more about Dipti →